I've written a notebook containing a model and training code for a deliberately-simple character-level Mixture-of-Experts Transformer model.

I've removed as many complications as I can from it while still retaining better performance on a per-FLOP basis than a similar dense Transformer. The only non-default dependencies are PyTorch, and WanDB.

The following explains how this model works, and how Mixture-of-Experts work in general.

(Note: The implementation is closest to a Switch Transformer. But it isn't really that. For instance, my implementation is trained solely on an autoregressive language modeling task, while Switch Transformer uses a masked token language modeling task; I use a different position encoding method; and so on. And a big chunk of the contribution of Switch Transformer is the routing across multiple GPUs in a particular way, while I completely ignore multi-GPU training or inference.)

Excessively Abstract Basics

Why would we care about MoEs?

Well, MoE Transformers generally take less compute than dense Transformers to be trained to any given level of loss.

Given that by now companies spend tens of millions of dollars on single Transformer training runs, reducing the GPU-hours required to reach some level of performance is obviously important.

MoE Transformers also reduce the compute required to do inference at some given level of loss.

They do both these things by reducing the per-parameter compute per forward and backward pass of a Transformer, through "hard" sparsity.

That is, a standard Transformer must do some operation for every parameter, for every token, during a forward pass. A MoE lets you do some operation for only some parameters, for some tokens, during a forward pass. Put otherwise, a MoE lets you strongly decouple model size and compute spent in training. This is what lets a MoE trained with 10,000 GPU-hours have lower loss than a dense Transformer trained with 10,000 GPU-hours.

On the other hand, per parameter a dense Transformer will do better than a MoE Transformer. A dense Transformer with 7 billion parameters -- all of which are used per-token in each forward pass -- will generally have lower perplexity than a MoE transformer trained with 7 billion parameters -- only a fraction of which are used per-token in each forward pass. But -- if it's cheaper, no one cares about how many parameters it takes.

Mildly Less Abstract Basics

(I assume you already know basically how a Transformer works. If you do not, this is my current favorite explanation.)

Most non-MoE Transformers -- most "dense" Transformers -- are composed of N architecturally identical residual blocks. The input to each layer -- during training --- is a tensor with dimensions like [batch_size, sequence_length, token_embed_dim].

Each residual block within a Transformer has two sub-parts, which are also residual.

- Attention, that mixes data over the time dimension

- A MLP / feedforward part, that transforms data within the time dimension.

The attention mixes information over time -- thus, the output of each time-slice in an autoregressive Transformer depends on all prior time-slices. The MLP / feedforward part ignores time -- altering any time-slice input passed to the MLP leaves the others entirely unchanged.

An implementation of a forward pass of a Transformer block in PyTorch thus usually looks something like this:

def forward(x):

# x has shape [batch, length, hidden_dimension]

x = x + self.attention(self.some_normalizer1(x))

x = x + self.mlp(self.some_normalizer2(x))

return x

To turn a Transformer block composed of these two sub-parts into a MoE block, you replace the MLP / feedforward part with a "mixture-of-experts" component, while leaving every other part of the Transformer block unchanged.

def forward(x):

x = x + self.attention(self.some_normalizer1(x))

x = x + self.SOME_MOE_LAYER(self.some_normalizer2(x))

return x

(Note that there are ways to incorporate mixtures-of-experts into the attention as well, although in the "standard" MoE design, the attention remains entirely untouched. Not that there really are definite standards at the moment.)

A slight wrinkle here is that MoEs need an auxiliary loss added to the cross-entropy loss on which a language model is generally trained. This auxiliary loss helps "balance" the experts within the Mixture-of-Experts layer -- more on how you calculate this later, and why this matters.

For now, what matters is that this auxilliary loss has to be handed down through the residual stack of the Transformer. So the actual implementation of the residual Transformer block for a MoE might look a little more like this.

def forward(self, input_tuple):

x, aux_loss = input_tuple

x_att = self.attention(x)

x = x + self.norm1(x_att)

x_ff, aux_loss = self.MOE_LAYER((x, aux_loss))

x = x + self.norm2(x_ff)

return x, aux_loss

However -- it is pretty important to note that (usually) a MoE Transformer does not replace every layer of a Transformer with the above MoE block layer.

The convention is -- generally -- to replace every other layer of a Transformer with a MoE layer -- this is what GShard and the Switch Transformer do. The other layers remain the same -- except for some modification that lets them hand down the auxiliary loss.

But although this every-other layering is the convention, there's no necessity to it -- OpenMoE replaces every 4th layer or every 6th layer with a MoE layer. Or "Scaling Vision with Sparse Mixture of Experts" notes in an appendix that MoE Transformers with MoE layers only in the second half of the Transformer layers seem to work as well (or sometimes better) than Transformers with MoE layers throughout. I've found this as well:

# If 'layers' determined which of your transformer layers

# use normal 'mlp' blocks or 'moe' blocks, then rather than doing:

layers = ["mlp", "MOE", "mlp", "MOE", "mlp", "MOE", "mlp", "MOE", "mlp"]

# I have instead had good results with something like:

layers = ["mlp", "mlp", "mlp", "mlp", "mlp", "MOE", "mlp", "MOE", "mlp"]

But there are also cases where it's alright to have a MoE layer in every Transformer block. For instance, the Mixtral-of-Experts, has a MoE in every layer. But this is probably something enabled by how Mixtral-of-Experts was initialized with the fully-trained weights of a smaller model.

Anyhow, I don't know of any rigorous justification for which layers to change to MoE layers. We await actual science on the topic. But while training from scratch, I've found that you at most want to have a MoE layer for every other dense layer.

Mixture-of-Experts Layer

Okay, how does the MoE layer itself actually work? We know that our residual Transformer-block implementation will take a (tensor, aux_loss) tuple. But have not actually gotten into how it is implemented.

A mixture-of-experts layer has inside of it:

- Some number

Nalmost completely standard MLP layers, the "experts". The only way in which each expert differs from a normal MLP layer, in our implementation, is that they have smaller weight initializations. This is pretty typical -- they're usually just standard MLP layers. - Some gating layer, that for each token will map to one (or more) of the

Nexperts. This expert is usually parameterized with a linear layer from the residual dimension of the Transformer to the number of experts.

In our MoE PyTorch implementation, each token will be routed to exactly one of the MLP experts. The output of that expert, given that token, will then be the complete output for that token for the entire MoE layer.

(By following the Switch Transformer in this respect, this means that if we ignore the compute involved in calculating the gating layer, which is quite small -- then the MoE Transformer does the same number of operations per forward pass as a Dense transformer whose MLP layers are the same size as each expert. This is convenient for equi-FLOP comparisons.)

But -- it is important to note that there are other ways that other MoE implementations handle the routing.

Rather than routing each token to exactly one expert, you could also route each token to 2 or 3 experts. You could then add the output from each expert MLP, and make this sum the output of the MoE layer. So for instance in Meta's "Efficient Large Scale Language Modeling with Mixtures of Experts" they route each token to the top 2 experts.

Alternately, rather than routing each token to a fixed number of experts, you could say that each expert receives a fixed number of tokens. This means that some tokens could be routed to 4 experts -- and others routed to 0. This is called "Expert Choice Routing"and it looks interesting, but it doesn't play as well with causal language modeling.

Implementation

The actual implementation of this gating is a linear layer mapping from hidden_dim to num_experts followed by a Softmax. I follow Switch Transformer in adding some uniform multiplicative noise, to encourage "exploration" to find the best expert per-token.

We can initialize the MoE layer as follows:

class SwitchMoE(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config, index):

super().__init__()

self.hidden_dim = hd = config["hidden_dim"]

self.num_experts = num_experts = config["num_experts"][index]

self.moe_scaling = moe_scaling = config["init_moe_scaling"]

self.experts = nn.ModuleList([

MLP(config, index=index, scaling=moe_scaling)

for index

in range(num_experts)

])

self.gate = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(hd, num_experts),

UnitCenteredNoise(scaling=0.02),

nn.Softmax(dim=-1)

)

What hidden_dim and num_experts are should be pretty obvious. The variable moe_scaling is some float like 0.1, which scales down the weight initialization for each of the experts.

What about UnitCenteredNoise?

# Elementwise multiplies: x * (1 +- eps)

class UnitCenteredNoise(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, scaling=0.02):

super(UnitCenteredNoise, self).__init__()

self.scaling = scaling

self.base = 1 - (scaling * 0.5)

def forward(self, x):

if self.training:

# uniform 1-centered noise

noise = torch.rand(x.size()).to(x.device)

noise_centered = (noise * self.scaling) + self.base

return x * noise_centered

else:

return x

So this just applies a little elementwise multiplicative jitter to whatever is passed to it.

Ok, how does this actually work in the forward pass, then?

Well, in the forward pass we use the gating function to generate a one-hot encoding for each token, indicating to which expert that token will go.

def forward(self, xx):

inp, aux_loss = xx

b, t, c = inp.shape

# Reshape to [b * t, c] for fun

inp = inp.reshape(b * t, c)

# [b * t, c] -> [b * t, num_experts]

gate_val_continuous = self.gate(inp)

# [b * t, num_experts] -> [b * t, 1]

_, gate_val_indices = torch.topk(gate_val_continuous, 1, dim=-1)

# Map [b * t, 1] to the one-hot encoding [b * t, num_experts]

one_hot = torch.nn.functional.one_hot(gate_val_indices, num_classes=self.num_experts).sum(1)

Thus, even though the parameterization that selects each expert is continuous, each expert receives just one token.

Having created a one-hot encoding for each token, indicating to what expert that token should be routed, we still need to feed those tokens (and only those tokens) to the corresponding expert.

We can do this by making a boolean mask with the same dimensions as the input. We select the relevant tokens, feed them into the expert, and then add them to the output.

output = torch.zeros_like(inp)

for i in range(self.num_experts):

mask = one_hot[:,i] == 1 # mask shape: [b * t]

mask_expand = mask.unsqueeze(-1).expand_as(output) # to [b * t, c]

inp_for_expert = inp[mask_expand].reshape(-1, c)

out_from_exp, _ = self.experts[i]((inp_for_expert, torch.zeros([1])))

output[mask_expand] =+ out_from_exp.reshape(-1)

return output.reshape(b, t, c), extra_aux_loss + aux_loss

This is pretty slow. Ideally, we'd have code here offboarding the operations onto different GPUs.

Problem: Starving Experts

Imagine that, by chance, the router originally passes a handful more tokens to one expert than another.

This expert is then trained with more information than any other expert -- so it learns more. Shortly afterwards, the router picks up that, on average, loss is lower when routing tokens to this expert than to any other, and keeps doing this. The cycle repeats -- this expert keeps learning more, the others keep learning less. Soon, nearly all tokens get routed to a handful of experts while all the others starve.

This is one of the standard ways that MoEs fail to work.

To counter it, we need some kind of extra loss that punishes the router when it routes to various experts too unevenly. We if each batch has T tokens, we want each expert to on average get 1 / T tokens.

In this case, I again borrow the extra loss from Switch Transformer, but there are lots of variations.

Suppose we have N experts indexed from 1 to N, and a batch B with T tokens. Our auxiliary loss for this is the scaled dot-product of two vectors, (f) and (P) -- each of these vectors has length equal to the number of experts. The number (f_i) gives the fraction of probability-mass given to the expert (i), while the number (P_i) give the fraction of tokens given to the expert (i).

$$ loss = \alpha \cdot N \cdot \sum_{i=1}^{N} f_i \cdot P_i $$

This loss is minimized when an approximately equal number of tokens are sent to each expert. Alpha is set to some small number like 0.01, according to the Switch Transformer paper, although I've had more luck with numbers like ~0.04.

Given the gate values chosen above -- and excluding alpha -- we can calculate this very simply.

# Calculate auxillary loss to balance the experts

f = one_hot.sum(dim=0) # [b * t, num_experts] -> [num_experts]

f = f / f.sum()

P = gate_val_continuous.sum(dim=0) # [b * t, num_experts] -> [num_experts]

P = P / P.sum()

extra_aux_loss = (P * f).sum() * self.num_experts

In general, this loss is added to the cross-entropy loss during training.

In our PyTorch implementation, that means that instead of simply returning the residual tensor with dimensions [b, t, c] from each Transformer block, we need to return a tuple that has (tensor, extra_scalar_loss) as its members, as covered above.

Altered Learning Rates

Note that, if each batch has T tokens and we have N experts, each expert will -- on average -- see T / N tokens per batch. So there less data given to each expert per batch, by a factor of 1 / N.

So this amounts to an effective reduction of the batch size of 1 / N for each expert. Given that when we scale up batch size by N we should increase the learning rate by sqrt(N), this means that for each expert we should decrease the learning rate by 1 / sqrt(N).

So I follow "Efficient Large Scale Language Modeling with Mixtures of Experts" in shrinking the learning rate of each expert by this amount.

In my set-up, this seems to be mandatory -- if I don't do this then the MoE Transformer just doesn't work!

Altered Initialization

As alluded to above, I need to follow the Switch Transformer in shrinking the initialization weights of the experts by a factor of 10. This is the init_moe_scaling in the configuration above.

They find that if you don't do that, variance in performance jumps way up and average performance jumps way down; my experience confirms this.

(This might be an adaptation necessary only for MoE's that route to one-expert -- other works have found this to be unnecessary.)

The reason that the Switch Transformer paper says this is necessary is for "expert stability." Maybe this is so, but it feels like a, um, somewhat ad-hoc reason. Right now all I know is that the altered initialization seems useful for magical reasons.

Extra: Dropped Tokens

In practice while training non-toy models, different experts are instantiated on different GPUs. These GPUS can handle a finite number of tokens. During both training and inference, however, variable numbers of tokens will be sent to different experts.

At a minimum, we need each expert to handle the average number of tokens sent to each expert per batch:

$$ \frac{tokens\space per \space batch}{number \space of \space experts} $$

However, generally, each expert may have a few more or a few less tokens sent to it than the exact average. So for each expert we need to set the capacity factor, to determine how many more tokens can be sent to it than the average expert, before it starts dropping tokens.

$$ expert \space capacity = ( \frac{tokens \space per \space batch} {number \space of \space experts} ) * capacity \space factor $$

This isn't relevant to our implementation, but I'd be remiss if I didn't mention it.

Conclusion

Again, here is a link to a notebook containing the complete code.

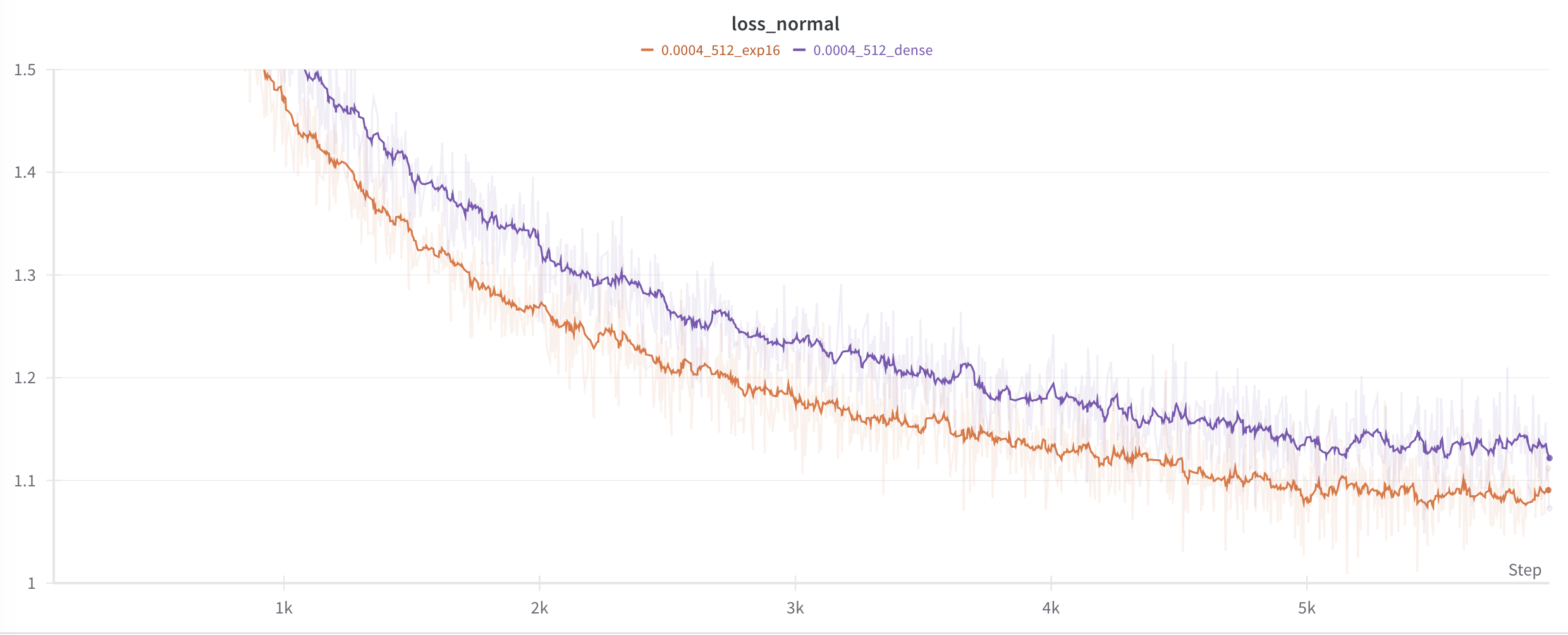

Here's one epoch of a MoE compared with a dense Transformer, run for 1 epoch on a 200mb text file scraped from Project Gutenberg.

In each case, the networks have 7 layers, a context size of 512 characters, attention with 8 heads, a residual dimension of 512, and a learning rate of 0.0004 that decays linearly to 1/10th of that. But in one case, the MLP layers in the 4th and 6th residual blocks have been replaced by a MoE with 16 experts.

So the dense Transformer has 20m parameters while the MoE has 85m. You can see how the MoE does better.